Utilizing a hedging strategy can help reduce the overall risk of a portfolio and control market exposure.

Consider, for example, the purchase of a put option in conjunction with owning the put option’s underlying asset. Buying a put option is similar to buying insurance for an asset. The owner of an asset is willing to pay money-- the put option’s premium--to help protect the overall investment from adverse situations, even if doing so increases the original position’s cost basis.

There are multiple ways to hedge a position and different reasons for hedging. If a position is showing an unrealized gain, a hedge may be used to secure profits at a specific price level. If an investor is afraid of losing money on an investment, a hedge could be put in place to protect the downside risk and limit risk exposure to a defined dollar amount or percentage of the portfolio.

Hedging can be accomplished using derivatives like options and futures contracts or through similar, uncorrelated, or negatively correlated instruments as the original position.

For example, if a stock is owned in the technology sector, an investor could short another stock in the same sector with a similar beta. This way, if the original position declines in price, the hedged position may experience a profit.

A negatively correlated position may also be opened as a hedging device.

For example, two tickers that have historically performed opposite of one another could be purchased simultaneously, so that if one asset declines in value, the other asset should increase in value.

Hedges do not guarantee that a loss will be avoided. It is nearly impossible to find a perfect hedge that minimizes all potential risks without forfeiting some or all potential profit. However, a balanced and diversified portfolio is considered an effective way to hedge multiple positions.

Hedge funds specialize in hedging opportunities. Hedge funds offer an investment vehicle with low market correlation to improve diversification and risk-management.

Hedging an investment portfolio is something many investors want to do, but few understand the mechanics or take the first step to actually do it.

Risk management seems prudent but falls low on many investors' to-do lists, especially during strong bull markets. However, protecting your positions from market turmoil is a key component of portfolio management.

What is a hedge?

A hedge is a position that offsets the risk of another position in a portfolio. A balanced and diversified portfolio is considered an effective start for hedging multiple positions.

The purpose of hedging is not to make money, but to reduce the overall risk of a portfolio and control market exposure. Hedging comes at a compromise of profit.

There are multiple ways to hedge and different reasons for hedging. Derivatives like options or futures contracts can be used to hedge a position.

Consider, for example, the purchase of a protective put option in conjunction with a long stock position. Buying a put option is similar to buying insurance for the stock. You are willing to pay money-- the put option’s premium--to help protect the long stock position from a price decline.

Although the put option increases the stock’s cost-basis and reduces the maximum profit, it protects the position’s downside and defines the maximum loss.

Hedging can also be accomplished through uncorrelated or negatively correlated assets. Correlation is a historical measurement of how two securities moved together in the past.

For example, if you own a stock in the technology sector, you could short another stock in the same sector with a similar beta. If the original position declines in price, the hedged position will likely increase.

A negatively correlated position may also be used as a hedge. For example, gold and the US dollar have historically performed opposite of one another. The two securities could be purchased simultaneously, so that if one asset declines in value, the other asset should increase in value.

Hedges do not guarantee that a loss will be avoided. It is nearly impossible to find a perfect hedge that minimizes all potential risks without forfeiting some or all potential profit.

What is the difference between hedging and diversification?

Diversification is a form of hedging and is key to a balanced portfolio. A mixture of diverse securities minimizes the unsystematic risk associated with allocating capital to a single stock or sector and reduces the effects of market volatility.

The goal of diversification is to combine uncorrelated assets to smooth returns. Diversification allows investors to construct a portfolio that maximizes return while limiting risk by varying asset allocation to help reduce the risk of individual security price fluctuations.

As with any form of hedging, diversification comes at a compromise of total profit potential. In theory, diversification works because some assets will perform well while others underperform.

When you think of hedging, you should think about a hyper-focused risk reduction event, where you're offsetting risk for a specific event, outcome, or time, not overall risk like with diversification. When hedging an asset in a portfolio, you are trying to invest in products with a strong, predictable, inverse correlation. The assumption is that if one asset goes down, the other will go up and offset the loss.

Listen to this Option Alpha podcast to learn more about the hedging vs. diversifying.

Why diversification alone is insufficient

When volatility increases, investments tend to move in sync with one another, thus rendering diversification less effective when markets crash.

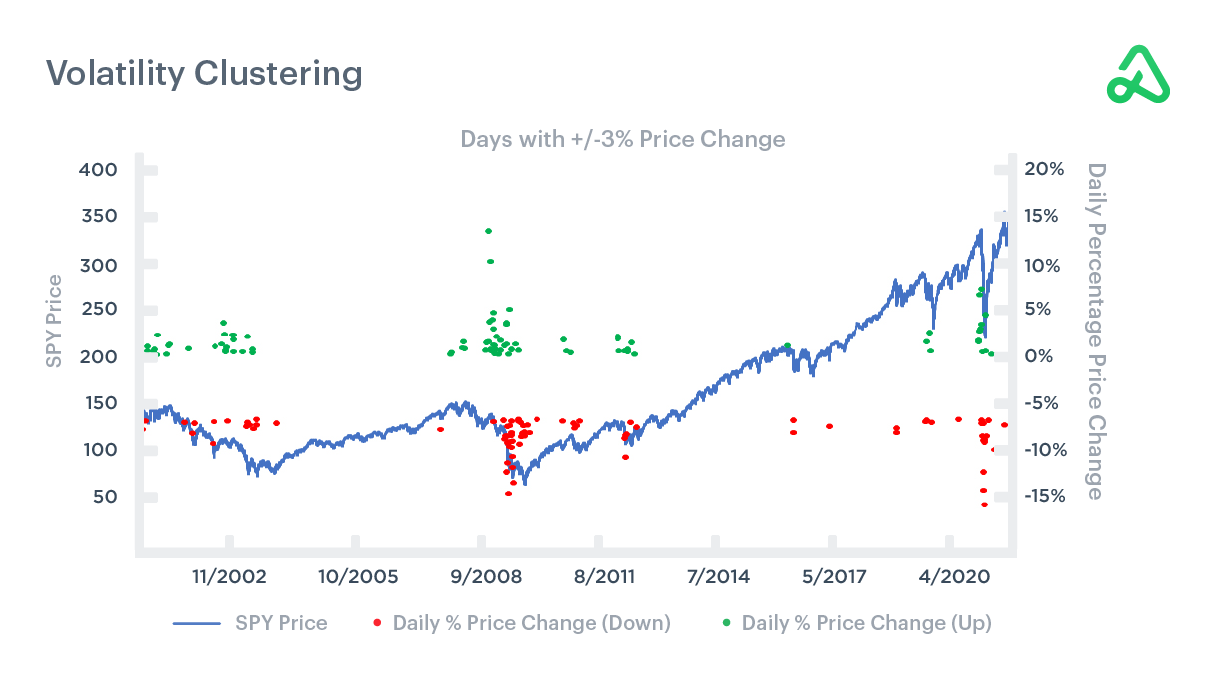

Volatility clustering is the tendency for large movements in security prices to group together and promote similarly volatile moves in the immediate future.

When volatility increases, securities autocorrelate as assets with little or no previous correlation suddenly move in sync with one another, reducing or eliminating the benefits of diversification when markets crash.

From 2000 through 2020, SPY went through prolonged periods with no daily price changes of +/-3%. However, once volatility entered the market, it was a constant presence until late in 2011, when the market returned to many years of low volatility.

Why should I hedge my portfolio?

You should hedge your portfolio because market drawdowns happen more frequently than you might think and they seem to happen when it is least advantageous for your portfolio.

The chart below shows drawdowns from 52-week highs from September 2001 to September 2021. Despite a strong uptrend for the majority of the 20-year lookback period, a market decline of 10% or more occurred almost annually.

Short-term volatility can often shake many investors out of long-term trends.

How would you react to a 10% market drawdown? Could you hold through the volatility? Would you be willing to pay a small premium to help offset that loss?

Investors often skip hedging because of the potential drag on portfolio performance and the relatively high cost of some hedging strategies. Simply put: when everything is going well, hedging is a drag on portfolio performance.

However, the key to hedging (and diversifying) is to approach it consistently and mechanically. While the short-term cost of hedging may impact your portfolio returns, the purpose is to protect your investments from unpredictable black-swan events.

Further, volatility clustering and autocorrelation make some investors think any hedging strategy is futile. If correlations break down when you need the protection most, why hedge at all?

For some relatively conservative options portfolios, even moderate drops in the overall market can lead to a severe portfolio drawdown.

For example, a portfolio 50% allocated to options selling strategies such as vertical spreads, iron condors, and iron butterflies may drop more than 20-30% when the market falls 10%. A more aggressive options portfolio could drop 50% or more during the same market decline.

Perhaps the most significant reason to hedge is to smooth your equity curve. Reducing your drawdowns amplifies the benefits of compounding--not to mention the reduced stress!

Consider two unique investor scenarios. Investor O invests $10,000 and has annual returns of -10%, +10%, and +10%. Investor A invests $10,000 and has annual returns of -20%, +10%, and +10%.

After three years, Investor O has $10,890 while Investor A has $9,680. Investor A is still trying to overcome the early drawdown, while Investor O is already reaching new highs. Large percentage drawdowns require even larger percentage climbs to break even.

Hedging does not replace other risk-management tools such as position sizing, maintaining cash reserves, laddering entries, dollar-cost averaging, or diversification.

The goal of risk management and hedging is to survive so you can thrive.

By dramatically reducing the probability of suffering a loss you cannot recover from (“risk of ruin”), your portfolio can weather the market’s storms and live to fight another day.

How do I hedge my portfolio?

Hedging your portfolio is a multi-step process involving multiple considerations.

Determine risk tolerance

How much of a portfolio decline can you tolerate? Is it a 10% drop, a 20% drop, a 50% drop, or somewhere in between?

Once you have determined your risk tolerance, you can begin constructing a hedge to protect your portfolio from a drop below that value.

Remember, the smaller the decline you are willing to accept, the more expensive the hedge and the greater the drag on portfolio performance during periods of rising prices.

Portfolio composition

What has a negative correlation to your portfolio? Similar to the concepts of beta weighting or maintaining a neutral portfolio, a hedge should offset the potential negative effects of directional bias or volatility exposure.

If your portfolio has a strong bullish lean, the hedge you select should protect against market declines below the risk tolerance you determined in the last step.

Select a product

Choose a product to hedge against an opposing market move.

Continuing the example of hedging a bullish portfolio, you could use put options, inverse ETFs, negatively correlated securities, or a combination of hedges.

This is where the possibilities are only limited by your imagination. For example, you could select long put options with a variety of deltas to hedge different risk tolerances. A relatively high delta, protective put strategy with enough contracts to limit losses for your entire portfolio is an aggressive hedge that will be expensive to maintain.

In contrast, a low delta, “Doomsday Hedge” VIX call would be much cheaper to maintain, but will only limit losses in extreme tail-risk events.

Hedges are dynamic and can be strategy-specific. Not all hedges need to be in place when you enter a position. Hedging requires your active participation, whether it is a mechanical system or a proactive response to changing market conditions. It is important to be flexible and continuously assess your portfolio and add hedging strategies when necessary.

For example, a common hedge for a bullish put credit spread is to sell a bearish call credit spread when the put credit spread is challenged.

Combining the put credit spread and call credit spread positions has reduced your overall risk. The credit received from the call credit spread reduces the maximum loss of the put credit spread.

Inverse ETFs are designed to move opposite of the index they track. These products can be used similarly to put options, but are not adversely affected by time decay. You could use inverse ETFs or leveraged inverse ETFs, depending on how much capital you want to deploy for the hedge.

Although leveraged ETFs do not have time decay like put options, leveraged ETFs have their own drawbacks, like tracking error over prolonged periods of time.

Negatively correlated securities provide diversification and may offset losses across asset classes. While autocorrelation and volatility clustering are a real concern, negatively correlated securities are often used to provide protection in the case of moderate market declines.

Position Sizing

You need to choose the position size of your hedge. You are seeking to maximize the potential gain from the hedge while minimizing the potential drag on your portfolio performance.

Consider proportions for a hypothetical portfolio of $10,000:

- $9,000 of SPY and $1,000 of an inverse ETF provides a partial hedge.

- $8,000 of SPY and $2,000 of the inverse ETF provides a larger hedge.

- $9,000 of SPY and $1,000 of a leveraged inverse ETF.

The position size and proportion of hedge relative to portfolio exposure dictates the level of protection provided.

Entries and Exits

The timing or entry point for the hedge may inform the position sizing.

For example, you could perpetually hold put options that hedge tail risk, allocating 1-2% of your overall portfolio to the hedge at all times.

Alternatively, an investor may add an inverse ETF representing 10%, 20%, or more of their portfolio after a major index has fallen below a certain indicator, such as the 50-day simple moving average.

Many investors can see markets unraveling and detect the need to hedge. So, entries may not be the weak link in the chain. However, when to exit a short-term hedge can be confounding. Do you hold the hedge until the downturn reverses? Do you hold for a specific profit target or until expiration?

For entries and exits, backtesting cannot be overemphasized. Backtesting all of your hedging strategy’s components from position size to entries to exits builds confidence and provides a quantitative framework supporting the strategy.

Backtesting also helps you “trust the process” when the time comes. Market volatility can happen fast and catch you off guard. Being prepared helps you remain calm and emotionless when others panic.

Consistency

You must consistently deploy your hedging strategy. Sticking to your process is crucial because some hedges have to be in place well before market volatility arises.

Next Steps

This introduction to hedging is not meant to be prescriptive. It is here to help you think through important decisions along the way to protecting your portfolio. The need to hedge and the method for hedging are based on personal preferences.

While the specific hedging strategy deployed is a matter of personal preference, the logical steps to think through protecting your portfolio are consistent across hedging strategies.