An options contract is an agreement between a buyer and a seller that gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a specific asset at a specific strike price on or before a specific expiration date.

Options are leveraged financial instruments that derive their value from an underlying security. The underlying in an options contract is the security or asset from which the option derives its value.

Every option contract has an associated premium, or cost. A contract has three main components that determine the premium:

- Underlying Security’s Price

- Strike Price

- Expiration Date

The contract's strike price relative to the underlying security's price is the intrinsic value. Time remaining until expiration and volatility are the main factors of an option's extrinsic value.

The Options Handbook discusses options basics, options pricing, settlement, and exercise & assignment.

Options contracts

An option contract is an agreement between a buyer and a seller that gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a specific asset at a specific strike price on or before a specific expiration date. Options sellers are obligated to buy or sell shares of the underlying security per the options contract’s terms.

A contract has three main components that determine the premium:

- Underlying Security’s Price

- Strike Price

- Expiration Date

Call options

A call option gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy an underlying asset at a specific strike price on or before a specific expiration date. The buyer has the right, but no obligation, because he or she would only exercise the right if it is financially advantageous.

For example, if a buyer owns a call option that gives the right to buy shares of a company at $100 per share, and the company's stock is currently trading at $95, it does not make sense to exercise that right.

However, if the stock price is $105, the buyer could exercise the option and buy shares at the $100 strike price.

A call option seller would be obligated to sell the underlying asset at the contract’s predetermined strike price if the buyer chooses to exercise the option.

For example, if the buyer owns a call option that gives the right to buy shares of a company at $100 per share, and the company’s stock is currently trading at $105, the seller would be obligated to sell shares at $100.

Put options

A put option gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to sell an underlying asset at a specific strike price on or before a specific expiration date. The buyer has the right, but no obligation, because he or she would only exercise the right if it is financially advantageous.

For example, if a buyer owns a put option that gives the right to sell shares of a company at $100 per share, and the company's stock is currently trading at $105, it does not make sense to exercise that right. However, if the stock price is $95, the buyer could exercise the option and sell shares at the $100 strike price.

Conversely, the put option seller would be obligated through assignment to buy the underlying asset at the predetermined strike price if the buyer chooses to exercise the option.

For example, if the buyer owns a put option that gives the right to sell shares of a company at $100 per share and the company’s stock is currently trading at $95, the seller would be obligated to buy shares at $100.

Purchasing a put option is similar to short-selling a stock. The buyer of a put option is not required to hold the shares they have the right to sell, but margin requirements apply.

Strike price

The strike price is the specific price at which the underlying security can be bought or sold with an options contract. The strike price is also referred to as the exercise price.

For example, a call option with a $100 strike gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy the underlying security at $100 per share. Buyers of call options may purchase the underlying security at the strike price, while buyers of put options may sell the underlying security at the strike price.

The number and range of strike prices per expiration vary depending on the dollar price of the underlying security and the demand for the security's options contracts.

For example, some higher-priced stocks may have strike prices in $5 increments ($100, $105, $110, etc.), while some stocks may have strike prices offered in $1 increments ($50, $51, $52, etc.). Strike prices can be added as the underlying security's price changes and investor demand increases.

Expiration

The expiration date is the last trading day that an option can be exercised. If the option buyer does not exercise the option and the option’s strike price is out-of-the-money, the option will expire worthless.

If the contract is in-the-money at expiration and the option writer does not buy back the contract before the end of the trading day, the option will automatically be exercised and the seller will be assigned.

Expiration cycles

Expiration cycles determine when an options contract expires. The most common expiration cycles follow one of three cycles:

- Cycle 1 (January Cycle): Expires in January, April, July, October (the first month of each quarter)

- Cycle 2 (February Cycle): Expires in February, May, August, November (the second month of each quarter)

- Cycle 3 (March Cycle): Expires in March, June, September, December (the third month of each quarter)

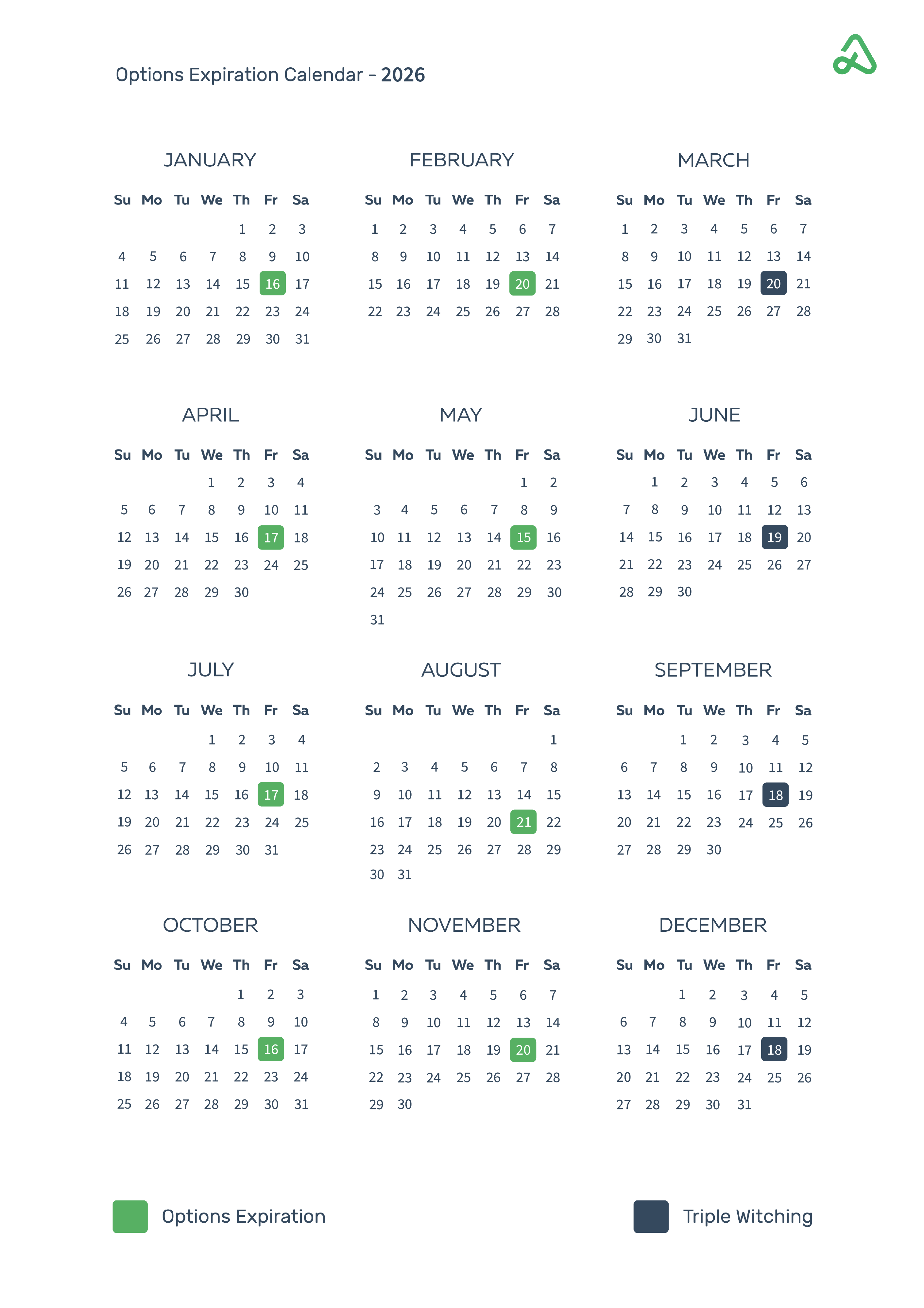

Options expiration for monthly contracts is the third Friday of the expiration month. If the third Friday is a holiday, the expiration for monthly contracts is on the third Thursday.

Triple witching occurs on the third Friday of March, June, September, and December when stock options, stock index futures contracts, and stock index options contracts expire on the same day once a quarter.

There are also weekly options contracts that expire on Fridays and, with some indexes and other underlying assets, expirations more frequent than weekly. For example, SPY, the SPDR S&P 500 ETF, has expirations on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of most weeks.

Long-Term Equity Anticipation Securities (LEAPS) have expiration dates longer than one year and are typically available in January and June one or more years into the future.

The number of expiration dates available depends on the liquidity of the underlying security. Securities with more trading volume typically have more expiration dates available.

Option premium

The option premium is the price of an options contract. Option buyers pay the option premium to the option seller at a mutually agreed-upon price in the open market.

An option contract's premium is the consideration given by the buyer to the seller to enter into the contract. The option buyer is paying a premium for the opportunity to call (buy) or put (sell) shares of stock.

Like auto insurance, where an insurance premium is paid and the driver has coverage in case of an accident for a specified period, option premiums provide "coverage" for a predetermined length of time.

The amount of premium paid depends on the contract's strike price, the time until expiration, volatility, and, to a lesser extent, dividend payments and interest rates.

Options leverage

Options contracts are leveraged financial instruments. One stock option contract is equivalent to 100 shares of the underlying asset. One equity call option contract gives the holder the right to buy 100 shares of stock. One equity put option contract gives the holder the right to sell 100 shares of stock.

Buying 100 shares of a $100 stock costs $10,000. A call option with a $5.00 premium costs $500 per contract. The leverage inherent in options enables an investor to have the same exposure for much less money.

Leverage increases both the profit potential and risk of an investment because any movement in the underlying security’s price can result in compounded changes in the option’s premium value.

Contract multiplier

The number of shares an options contract represents is also called the contract multiplier. Index options contracts and futures options contracts have different multipliers depending on the underlying asset.

For example, the contract multiplier for an S&P 500 Index (SPX) options contract is $100 x the value of the S&P 500, while the contract multiplier for a CME Group Crude Oil (CL) options contract is 1,000 barrels of oil.

Price quotes

Options price quotes are standardized and quoted in dollars and cents. For example, a call option may have a bid price of $1.00 and an ask price of $1.10. Options prices are quoted on a per share basis.

Because a call option represents the opportunity to buy 100 shares of the underlying security, a call option with an ask price of $1.10 would require $110 to purchase the contract. To determine how many dollars it would take to buy or sell a contract, multiply the bid or ask price by the contract multiplier.

Options price quotes typically contain additional details regarding the contract’s trading activity, including:

- Time of the last trade

- Last price at which the contract traded

- Bid price

- Ask price

- Difference between the option contract’s current price and the previous day’s closing price in numerical value and percentage change

- Volume at which the options contract is trading on that particular day

- Open interest

- Implied volatility

Option symbols

Option symbols are uniform and follow standards set by the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC).

Options symbols consist of four parts: the root symbol, the expiration date, the option type, and the strike price.

The root symbol is the underlying’s ticker symbol, such as AAPL for Apple; the expiration date contains the expiration year, month, and date; the option type uses a “C” for calls and a “P” for puts; and the strike price is the round dollar amount of the option’s strike price.

For example, the symbol for the January 21, 2022 SPY call option with a $300 strike price looks like this: SPY220121C00300000

Option class

Option class refers to all call options or put options for a particular underlying security. Options of the same type (calls or puts), underlying security, style (American or European), and contract size are of the same options class. For example, all SPY calls are one class of options.

Option series

Option series refers to all of the call options or put options with the same strike price and expiration date. For example, call options with the same exercise price and expiration are grouped as an options series. Options series are presented in options chains.

Option chains

Option price quotes are displayed in options chains where contracts are listed in order of expiration and strike price. Call options are typically listed on the left side of the option chain and put options are listed on the option chain’s right side.

Options chains provide an organized, visual display of available options for an underlying security. Options chains are shown in real-time and prices are constantly changing as buyers and sellers interact with one another.

Volume

Volume is the number of options contracts traded on a given day and is shown for each strike price for both call and put options. Volume shows investor demand and liquidity for an options contract.

As volume increases, the bid-ask spread typically decreases, which provides more efficient pricing. Volume is shown intraday on most trading platforms, and the volume count resets each trading day.

Open interest

Open interest is the number of active contracts outstanding. Open interest represents the number of options contracts for a particular class, strike price, and expiration date that are open and have not been closed or exercised. Open interest is updated daily and is typically displayed beside volume on most trading platforms.

The same options contract can be traded multiple times (volume). When a new contract is traded, open interest increases. Open interest can increase or decrease before expiration.

Bid-ask spread

The bid-ask spread is the price difference between the bid price and the ask price for a security.

The bid price is the price a buyer is willing to pay for a security, and the ask is the price a seller is willing to sell a security.

For example, consider the real estate market. Buyers submit bids at a price they are willing to purchase a property. Sellers offer an asking price at a value they are willing to accept. Price is negotiated until both sides mutually agree to an amount that satisfies both parties.

In an options price quote, the highest bid price and the lowest ask price are displayed for a security. The bid-ask spread is the difference between those two prices. If the bid is $1.00 and the ask is $1.10, the spread is $.10. The bid-ask spread decreases, or tightens, when increased volume helps create liquidity. The bid-ask spread increases, or widens, with lower volume securities. Tight bid-ask spreads are a hallmark of efficiently priced markets.

The midpoint, also known as the mark price, is sometimes also displayed. The midpoint is the price exactly between the bid and ask.

Order types

There are four different types of option contract orders. The type of order used depends on whether the order is opening a new position or closing an existing position.

The four order types are:

- Buy-to-open (BTO)

- Sell-to-open (STO)

- Buy-to-close (BTC)

- Sell-to-close (STC)

"Buy-to-open" and "sell-to-open" are used to initiate new positions. "Buy-to-open" orders are used to purchase a call or a put. "Sell-to-open" orders are used to sell a call or put. "Buy-to-close" orders are used to close positions that originated from a "sell-to-open" order. "Sell-to-close" orders are used to close positions that originated from a "buy-to-open" order.

When buying to open or close a position, the account will experience a debit (money is paid to purchase the contract). When selling to open or close a position, the account will experience a credit (money is received from the sale of the contract).

Consider these order types mathematically. Buying-to-open a contract adds a position to the account (+1). Selling-to-close a contract subtracts a position from the account (-1). Selling-to-open a contract subtracts a position from the account (-1), even if you do not currently hold the contract. If a contract is sold-to-open, the account is short the option contract. Buying-to-close a contract adds a position to the account (+1).

To close a position, choose the order type that offsets (brings to 0) the account exposure to an options contract.

Underlyings

The underlying in an options contract is the security or asset from which the option derives its value. Options contracts are derivatives because the value of the options contract is derived from the underlying security. The price of the underlying, also called the underlying instrument or underlier, is the primary driver of an options contract’s value.

Equity options

The underlying security for an equity options contract is the common stock or ETF of the options contract. For example, the underlying security for an Apple call option is 100 shares of Apple common stock. Equity options are deliverable; if the options contract is exercised, a physical settlement requires actual shares of common stock to be bought (call options) or sold (put options). U.S equity options have American-style options and can be exercised on any business day up to and including the expiration date.

Index options

A stock index option is an option on a stock market index. An equity index option’s underlying asset is a stock index, such as the S&P 500 or NASDAQ. Because indexes are not deliverable, index options are cash-settled. Whereas equity options represent 100 shares of common stock, an index option’s underlying value, and the basis for the cash settlement, is the index value times a multiplier--typically $100.

Index options do not give the buyer the right to purchase an index or sell the stock represented by the index. Instead, when exercised at expiration, index options are cash-settled if the contract is in-the-money. Index options can have either American or European-style options, but most index options, such as the CBOE’s SPX options, have European exercise. Index options typically have broader trading hours than equity options, and index options often have preferential tax treatment.

Futures options

Options on futures contracts are available across various asset classes, including currencies, interest rates, equity indexes, and physical commodities. Futures options may be deliverable with the underlying futures contract. For example, a gold futures call option gives the right to purchase gold futures at a specific price on or before expiration.

Expiration on futures options contracts is unique in that there are both A.M. and P.M. expiration times available for many contracts. Depending on the underlying futures contract’s expiration cycle, the options contract can have an A.M. (morning of the last trading day) or P.M. (close of the market) expiration. Cash settled futures contracts typically have an A.M. expiration.

Calculating gains and losses

Options contracts are leveraged and therefore have the potential for large gains and losses because any movement in the underlying security’s price can result in compounded changes in the value of the option’s premium.

One stock option contract is equivalent to 100 shares of the underlying asset. Therefore, if a trader buys-to-open (BTO) a call option for $2.00 per contract ($200 invested) and sells-to-close (STC) the contract for $2.50, the gain on the trade would be $50 ($2.50 - 2.00 = $0.50 x 100 = $50).

Similarly, a trader can sell-to-open (STO) a contract at $2.50 and subsequently buy-to-close (BTC) the contract at $2.00 for a $50 profit. A trader may close a position at any time before expiration or assignment to realize a profit or minimize a loss (except for European-style options).

When purchasing an options contract, the risk of loss is limited to the initial premium paid, and the profit potential is unlimited. An out-of-the-money options contract that is not exercised or sold before expiration will expire worthless. If an option is in-the-money at expiration, the investor may choose to sell the contract back to the market or exercise the option, buying or selling 100 shares per contract.

When selling options, the loss depends on the type of contract (call or put) and the strategy used. The maximum profit potential for a short option is the initial credit received when the position is opened.

If an option is in-the-money as it approaches expiration, the option writer will need to exit the position if they do not want to accept assignment of the underlying security. Any options contract (including European-style options) may be bought or sold to close the position before the expiration date. The profit or loss will depend on the difference between the entry and exit prices.

Exercise and assignment

An option buyer (or holder) has the right to exercise an options contract. Option sellers (or writers) may be assigned exercised options contracts. Exercise and assignment are the two sides of the same transaction.

Exercising options

Options exercise is the process by which the buyer of an option submits a request to his or her broker to exercise an options contract’s rights. An option holder may exercise his or her stock option at the option’s strike price. For example, an investor who owns a long call option may choose to exercise the option and buy shares at the strike price.

The timing of the exercise’s timing depends on the option contract’s specifications: American or European-style option, the underlying’s current price, the option contract’s strike price, the length of time remaining on the options contract, and the option holder’s outlook for the underlying security.

For options contracts that do not have physical delivery of the underlying asset (shares of stock, barrels of crude oil, etc.), the exercise settlement value is determined at expiration, and a cash settlement amount is calculated.

American and European-style options

American and European are the two styles of options contracts. The two styles specify when the options contract can be exercised and have nothing to do with a geographic region. American-style options contracts can be exercised any day on or before the expiration date. For example, U.S. equity options are American-style options.

European-style options contracts can only be exercised on the expiration date. Many index options are European-style options. European-style options cannot be assigned early to the option seller.

Options assignment

Assignment is the fulfillment of the contractual obligation of the contract’s terms. An option seller is obligated to complete the requirements of the options contract--whether that is to sell shares of stock at the strike price (call option seller) or purchase shares of stock at the strike price (put option seller). The buyer of an option exercises his or her rights as the contract holder, and the option seller fulfills his or her obligation as the contract writer.

For example, the buyer of a January Netflix (NFLX) $400 call option has the right, but not the obligation, to exercise his or her right to purchase 100 shares of NFLX at $400 from the option seller on or before expiration in January. If the buyer exercises the options contract, a seller will be assigned the obligation to sell those 100 shares of NFLX at $400.

The Options Clearing Corporation (OCC) randomly selects a brokerage firm (a clearing member with the OCC) for the assignment, and that firm will randomly select an individual for assignment from an account that is short the options contract.